‘Onward Singapore’ says the national anthem, and judging from the view from my balcony, it’s going also upwards and sometimes sideways. It’s hard to keep up with the speed at which this country changes. Having moved to a part of town dominated by rainforests three years ago, we now live in a massive construction site of high rise buildings. Also the next door neighbour has torn his house down and is rebuilding it from scratch. This is Singapore, continuously developing and striving towards modernity ever since its independence 50 years ago this summer. This birthday has not gone unnoticed to anyone who lives here. There was a certain solemnity following the passing of founding father and prime minister of more than three decades, Lee Kuan Yew (LKY), in March. This has been followed by a massive build-up to the two main national events of the year: the South East Asian (SEA) Games this June, and the extended National Day celebration in August.

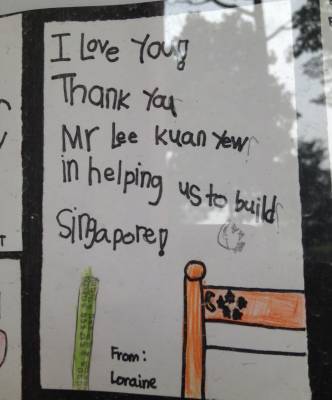

A child’s message to the late Lee Kuan Yew

A nation (at least in the contemporary interpretation) is a group of people sharing a geographical area and a common government. The more diverse the population, the more effort has to be made to build a nation and to secure its sustainability, a significant challenge for Singapore which has barely any natural resources. Despite this, Singapore has fully realised the potential presented by its strategic location. It’s an ideal hub in the Asia-Pacific region, with a highly skilled workforce and efficient bureaucracy, made possible by a quality education system for the multilingual population. So how has this nation come about and transformed itself into what we see today?

It was by no means obvious that Singapore was going to be an independent country. Britain’s long-term plan was limited self-government under continued colonial rule, partly to further British geopolitical and financial interests in the region, and partly for fear of Singapore becoming communist. (1) This was achieved in 1955, followed by the first parliamentary elections which brought the People’s Action Party (PAP) under LKY to power. But despite Britain’s plans, Singapore soon embarked on the first step towards independence: merger with the newly independent Malaysia in 1963. There are different interpretations of LKY’s actions at this time, but the result was ‘piggy-backing’ on Malaysia’s independence (orchestrated by Britain). The union lasted only two years. Due to fear among Malays that the Chinese-dominated Singapore and its PAP government would become too dominant, Singapore was excluded and LKY famously broke into tears on TV. A small island of Chinese dominance in a sea of potentially hostile neighbours was now a country in its own right. LKY then had to step up – whether he wanted to or not is disputed – to make sure that there was internal order as well as defense against external threats, nationalism and communism being two of the main ones.

The world into which this island nation was born in 1965 was anything but peaceful; the Vietnam war and, more importantly, the Chinese Cultural revolution were in full swing. China attempted to influence the young nation by broadcasting communist propaganda and encouraging the development of a people’s republic in Malaya (including Singapore). This aggressive propaganda was perceived of as a threat by the leadership under LKY. In addition, internal unity was a challenge to this immigrant society. Most Singaporean residents were traditionally there for a limited period of time, and even if they ended up staying their whole life, their national allegiance was usually somewhere else. Most new Chinese immigrants were more interested in the affairs of their villages back in China, while many Straits Chinese who had lived in Singapore for generations and had intermarried with the local population were loyal to the British crown. Singapore was a destination, be it long- or short term, but it was not home to most people. So how could this be changed, how could Singapore become a home for its people?

Early HDB block in Singapore’s Kallang neighbourhood

Well, for starters, people quite literally needed homes. At the time of independence, 1.3 million people lived in shacks and huts across the island, with very few amenities and services. This all changed when the Housing Development Board (HDB) was founded in 1960, as one of the first efforts of the new PAP government. Over the next 20 years, this institution would house 2 million people. Today, around 90 percent of the population live in HDB flats and Singapore has one of the highest rates of home ownership in the world. This was a major achievement in the process of nation building; it was not only about providing citizens with running water, electricity and communal services, it was also an integration project. People of different ethnic groups were placed within the same housing estates for community building purposes. It was part of the greater effort to build a Singaporean identity, and to prevent disparate ethnic and cultural identities from dominating society.

Other nation building initiatives taken by the government in these early years included a national education system (versus those provided by religious or cultural institutions), national service for all young men (of all ethnic groups), and other outward expressions of patriotism in society, e.g through reciting the national pledge and singing the national anthem. A deliberate way of forging unity and creating a distinct Singaporean identity are the national symbols; the national anthem ‘Onward Singapore’ (in Malay to reflect the native language of the land), the flag, the pledge and the seal are all symbols used by the government to unite the people, with the general message of striving for happiness, prosperity and progress together.

Supermarket taking part in the nationalistic celebrations

Nation building is an expensive and necessarily inclusive endeavour. Singapore’s recipe: making the best use of its strategic location, and thereby attracting foreign capital; ensuring a smoothly operating business environment with an efficient bureaucracy, infrastructure and low taxes; and developing a symbiotic relationship with the population, a mutually beneficial social contract. The government also focuses on inclusive economic growth, meaning growth that benefits everyone, in the form of pensions (2), healthcare, education and low corruption. It does, however, expect a dutiful population to follow its lead into a prosperous future, often achieved through innumerable campaigns telling people to wash their hands, flush the toilet, be kind to each other, cut your hair, buckle up, save water, eat healthy, breastfeed, don’t smoke, don’t litter, speak Mandarin and don’t have more than two kids. One of the current campaigns seeks to acknowledge the “Pioneer Generation” as the nation builders, offering subsidized medical care for the elderly, and even the opportunity to cut the queues in the grocery store. We may see more of such inclusive measures in the coming years. For example, one group in need of support are the young, who will struggle to leave the nest due to financial constraints, not least rising housing prices.

Despite its many successes, there is no shortage of criticism of the Singaporean brand of nation building, mostly from Western countries, but also increasingly from Singaporeans who feel they get less than their fair share. Descriptions such as “Disneyland with the death penalty” are very misleading, because it takes two rather peripheral and extreme aspects of a country (the ultimate fun and the ultimate opposite) and suggests these represent the whole. Still, punishments can be harsh, (including caning and death penalty for non-violent crimes), while civil and political rights and freedoms are curtailed, with the media landscape managed by the government. There are limited checks and balances within the government system itself, and excessively overpaid civil servants upset many Singaporeans who consider it ‘open corruption.’ Even though the effort of uniting ethnic groups may have been relatively successful, there is an increasing gap between rich and poor. Singapore manages 5 percent of the world’s total private wealth, and the low-tax environment enables pro-rich growth. Inequality is rampant, spurred by influx of wealthy foreigners and the elaborate lifestyle of rich Singaporeans, leaving the poor – and even the middle class – with high living costs and limited means of supporting their families and ensuring a better future for their children. This is especially challenging in this exceptionally consumerist society, affecting people at all levels of of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Singapore may be developed, it has come from “third world to first,”(3) but only just. The country has yet to really reach post-modernism, even though experiments with alternative lifestyles exist to a limited extent.

There are lessons to be learned from Singapore’s extraordinary development, both from the successes and the failures described above. It has incorporated an unusual combination of pro-market policies, along with social policies for the majority of the population to drive stability and inclusive growth. It recognizes that nation building is a continuous task, as transient workers and professionals still make up a sizeable proportion of the population – 40 percent of the people who live in Singapore today were born elsewhere! This, in addition to the already diverse citizenship, makes national identity a continuous challenge. Perhaps, most importantly, Singapore is committed to continuous improvement: The goals of the national pledge – happiness, prosperity and progress – have yet to be met, so there will be more striving for ‘onward Singapore’ in the next 50 years.

Your occasional correspondent is looking forward to being part of it. And for the construction next door to finish so I can enjoy my balcony again.

(1) This fear was caused by a strong allegiance of Chinese workers with the Malayan Communist Party, and a certain pride of overseas Chinese of Mao’s communist revolution in mainland China. The Singaporean political and financial elite would not let this happen.

(2) The government pension system has come under scrutiny in recent years, partly due to its link to the housing market as people can use their pension fund to buy housing.

(3) Title of Lee Kuan Yew’s memoir

————-

Links:

Government campaigns of the 70s and 80s

http://remembersingapore.org/2013/01/18/singapore-campaigns-of-the-past/

History of Singapore – BBC Documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShHakZOV2Tc

Singapore and the Asian century – The Diplomat

http://thediplomat.com/2015/02/singapore-and-the-asian-century/

The Housing Development Board

http://www.hdb.gov.sg/fi10/fi10320p.nsf/w/AboutUsPublicHousing?OpenDocument

Young people’s financial situation in Singapore

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101340730

Singapore’s development in indicators

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f902856e-d126-11e4-86c8-00144feab7de.html#axzz3dC779NtA

The complexity of Singaporean pensions

http://m.todayonline.com/singapore/why-its-so-hard-sporeans-understand-cpf